FlyPast Magazine June 2005

|

|

A WORLD-renowned institution links two elements of Peter Vacher’s life. This is Rolls-Royce, a name synonymous with precision and quality. Peter has taken the step from restoring classic Rolls-Royce cars to acquiring, restoring and now operating a Hawker Hurricane I – powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin III. After passing his driving test at 17, Peter bought a 1934 Standard Nine for £10 and started to learn about cars by looking after it and repairing it. Restoring motor cars became a hobby for him and he describes the process as “a real passion”. |

Peter’s 1926 Silver Dowry car, built for a Maharaja’s wife, following its painstaking restoration. |

He developed a particular love for Rolls-Royces of the 1920s and 1930s. In 1970 Peter acquired a bare chassis and completed a restorations – he still has that one. Another project was a 1922 Silver Ghost which had previously been in use as a breakdown truck. His last restorations was a 1926 Silver Dowry car, built for His Highness the Maharaja of Bharatpur as a gift for this wife. It was exported through Nepal in 1983 in poor state and described – pretty accurately – as “automotive spare parts”. It languished in store in the UK for a while and then Peter came by it. An epic eight-year restoration has resulted in a work of art. INDIAN CONNECTION At Varanasi, the Banaras Hindu University was on their ‘hit list’. It was known that the school had cars for technical instruction. To their delight, they found a Silver Ghost and Phantom I. Alongside the workshop holding the cars was a walled compound. Just visible above the wall was a cockpit. Inspection found this to be from an intact, but very forlorn-looking Hurricane. At this stage, Peter had no interest in aircraft and thought no more about it. A job in academic publishing took Peter and his wife Polly to Australia in 1993. It was then that Rolls-Royce and aircraft fused, and Peter remembered the Hurricane sitting in a yard in India. But I couldn’t possibly still be there could it? John and Peter went back to Varanasi in 1996. It was still there and they made an approach to purchase it. Peter could not have realised it at the time, but “undoubtedly the most difficult part was getting it out of India”. What followed was “a six year saga of negotiations” and no less than ten visits to India. Peter related a delightful story about a lighter moment in the grinding and pendulous process to acquire the Hurricane. He was becoming frustrated at never ending levers of bureaucracy that unfolded with seeming ease time after time. Well miffed with another turn and twist in the process, Peter threw his hands in the air and bemoaned Indian officialdom. A sage-like voice came from the other side of the desk with a question: “And who taught us bureaucracy?” Well, the ‘Brits’ of course. Touché. Then, out of the blue, in 2001 came a “yes you can have it but it must go before the students come back”. Great, thought Peter. Then he was told that would be the following week! The removal from the compound is a story in its own right and you must turn to Peter’s book Hurricane R4118 for details of what became a part comedic, part tragic, wholly traumatic experience. During this the Times of India started a campaign to have the export halted, although this particular airframe held practically no significance to the national heritage, whereas the university certainly stood to benefit from the new equipment the sale would allow. |

|

No less than ten visits to India were required before R4118 could come home. Peter Vacher dreaming of the days when that cockpit would come back to life. |

The Hurricane as found, in the yard at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi |

Home at last! The centre section is unloaded |

Plates in the wing stamped with details of repairs undertaken by CRO workshops, including Taylorcraft at Rearsby |

THE BEST PART Once R4118 was back in the UK, Peter realised that uncovering every aspect of the aircraft’s past was by far and away “the best part” of the whole project. It had flow 49 sorties during the Battle of Britain, had been involved in five shoot-downs and at that time, five of its pilots were still alive. Peter started where most historians do when compiling the ‘biography’ of an aircraft, with the Form 78, what the RAF calls the Aircraft Movement Card – which charts the units or ‘keepers’, accidents, modifications and repairs. From the Form 78 the search for information, snippets and lead spread out like tentacles in all directions. With obvious delight, Peter showed me through just one element of the incredible research he has undertaken and which forms the basis of this book. The talked me though what he had learned from the study of just one element of his Hurricane: “the wings are so interesting”, Peter announced with glee. One of several accidents that befell R4118, necessitated the entire wing being replaced. Inspection of data plates on the wings tells a story. One plate carried LMSD/DDF/41H/xxxxx. Deciphering this took some time and as a consequence Peter became aware of the workings of an incredible operation – the Civilian Repair Organisation. CRO was a network of workshops and sub-contractors beavering away on parts, sub-assemblies or whole aircraft, getting them back into action as soon as possible. So what did the plate reveal? Hawker part numbers all have ‘41H’ as a prefix. The ‘CCF’ bit was Canadian Car and Foundry of Fort William, Canada. And ‘LMSD’? – London Midland and Scottish at Derby; the railway works rebuilt Hurricane wings for the CRO. So R4118 was fitted with Canadian-built wings for one of its repairs. But those wings had themselves been damaged, requiring repair at Derby. Across the whole airframe a series of part numbers have brought about blues to work carried out including PA – Parnall Aircraft of Yate, Glos and RAD – Rollasons of Croydon, Surrey. Two others, Peter has yet to ‘crack’ – ‘AF’ and ‘S2’ – can you help? Gloster built R4118 in the summer of 1940. ‘G5’ and ‘G8’ appear in many places. ‘G5’ was Hawker’s code for the airfield at Hucclecote, where R4118 first flew and ‘G8’ the massive factory at nearby Brockworth where it was produced. So what does a plate marked ‘DRLM G5 9201’ tell us? Well, we know the ‘G5’ bit. ‘DRLM’ is CRO member, David Rosenfield Ltd, Manchester. This company carried out repair work prior to the aircraft’s despatch to India in 1943. |

|

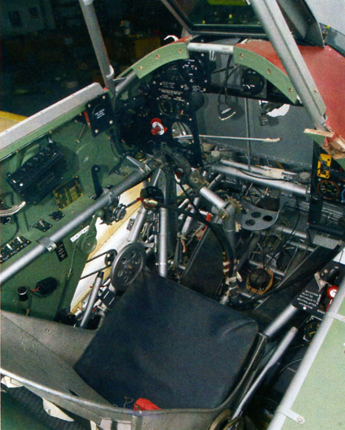

The cockpit during the final phase of restoration at the HRL workshop. |

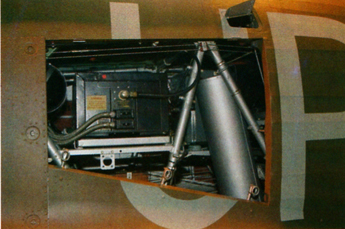

R4118's gun bay - a work of art |

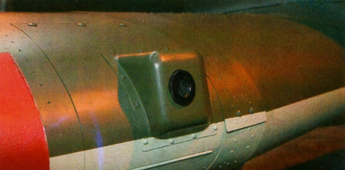

The camera gun installation on the wing leading edge |

|

The TR.1133 radio set in its bay within the fuselage |

Maurice Hammond (left) and Roy Nobel with the Merlin III |

BALLS IN THE AIR Likewise Peter would do the same with the engine restorations. This was placed with Maurice Hammond, well-known North American P-51D Mustang pilot and restorer, and a wizard with Merlins. Peter also set to the sourcing of parts, tracing suppliers, setting up exchanges for the bits needed and trying to keep a pace on the whole complex process. Finally, he was researching every element of R4118’s history and tracking down surviving pilots. From very early on, he had a book in mind – laying down the incredible provenance of this aircraft was “a vital element of getting the restorations right”. Peter summed up all this activity: “I’ve had to keep a lot of balls in the air”. |

|

| CONTINUED - PLEASE CLICK ON NEXT | |

| Back | Next |